The fight against diarrheal diseases in Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, cholera is endemic. And climate change is defiantly not helping to make things better. Rebeca Sultana has spent the last six years investigating diarrheal diseases including cholera transmission in a low-income urban community in Dhaka. A research team have developed the Cholera-phone – a mobile phone based community surveillance system to collect disease data – and she has calculated how much it cost to have non-severe diarrhoea (when you do not need to go to the hospital): 6 US dollars. And that is an important number to know if you want to mitigate this disease.

A six yearlong research project investigating cholera caused by climate change is coming to an end. The project has produced five PhDs and the final one is Rebeca Sultana with her project on ‘water usage, diarrhoea and the economic burden in a low-income urban community in Bangladesh’.

The research project is called the C5 project ‘Combating Cholera Caused by Climate Change’. It is a joint project between University of Copenhagen, University of Dhaka and International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b). It is a multi-disciplinary study started in 2013 that examines the risk and effects of climate-induced cholera on water stress on household hygiene in Bangladesh.

As an anthropologist, Rebeca is interested in learning more about context and the communities affected by the disease. What is the source of infection? How did it happen? How is it transmitted from one person to anther? And how is the community dealing with it all? These are the questions Rebeca tries to answer in her research.

Preventing faecal bacteria from entering the body

Preventive interventions to stop cholera bacteria from entering the human body has been going on for a very long time. Diarrheal disease transmission happens when a faecal bacteria enters a human host through a medium – often referred to as the five Fs of faecal-oral transmission routes: fluids, fingers, flies, foods, and fields.

“In preventive interventions you are working with two barriers with regards to transmission. The first one is about preventing faeces from entering the mediums. Therefore it is about improving water and sanitation infrastructure. In the secondary barrier, we try to prevent the contaminated mediums from entering the mouth. This is often the reality in low-income communities as they have poor water and sanitation infrastructure. Here, the interventions needs to focus on behavioural change, such as washing hands and other hygiene practices, as well as providing bacteria free water.”

In her thesis, Rebeca is criticising existing hygiene interventions that focus on the motivation to wash your hands. To her, hygiene is a social practice and we need to come up with new messages that will encourage people to practice good hygiene. Telling people that you will be germ free from washing hands is not enough.

Rebeca thinks we need to understand the social and cultural practices, if we want to come up with something different in order to prevent transmission:

“It is interesting to look at religious practices in relation to this matter. Muslim people who pray five times a day are using more water and they are much more concerned about their hygiene practices, and they are more conscious and careful, when they clean themselves for religious purpose. So incorporating religious perspectives as motivation of hygiene practices may help to improve hygiene practices instead of only aiming for germ free bodies as motivation, which should be explored in future effort” Rebeca argues.

When you work with post-outbreak interventions or disease preventive efforts in urban communities in Bangladesh, you need to design your messages to fit the community:

“Combine the biomedical knowledge and the community knowledge and translating both together to come up with a new knowledge, which is understood by both the public health research practitioners, as well as the local community you are working with, is essential. If the message is not clear, how will the practitioners working to prevent the disease be successful?” Rebeca reminds us.

In the last 30 years, we have seen numerous efforts when it comes to improving peoples’ hand hygiene and other hygiene practices. Globally, only 19% of people comply with hand hygiene recommendations. But Rebeca is hopeful:

“It's not easy to change peoples’ behaviour but I am sure that health and hygiene research, like the one we are doing here, will come up with some new technologies and methods, which will prove useful in terms of changing peoples’ hygiene practices.”

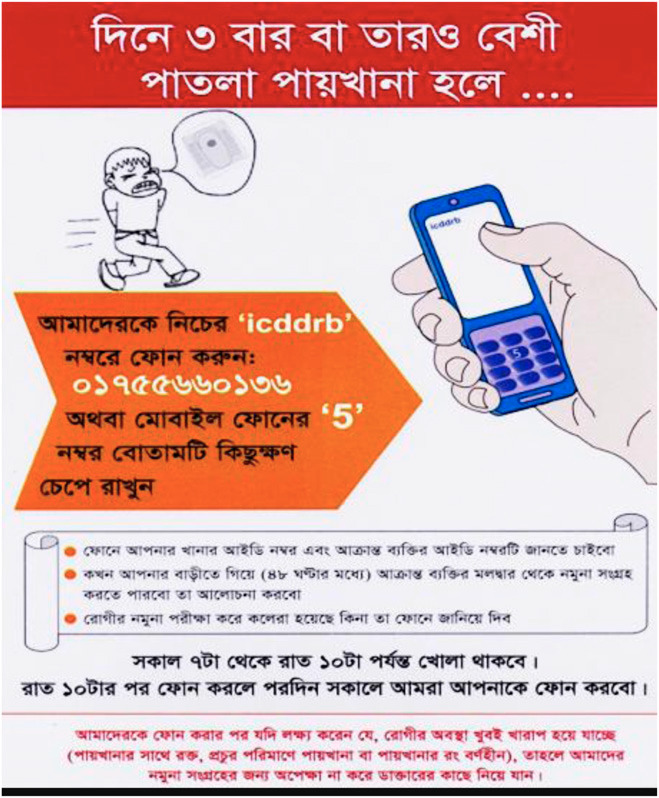

The cholera-phone

A research team including Rebeca came up with a community based surveillance system to detect disease. Using mobile technology for disease surveillance is not new but it is the first time it has been used to surveil diarrhoea and cholera at community.

“We came up with the Cholera phone – a mobile phone disease prevalence data collection system – that worked really well in combination with qualitative research. We gave the participants in the study a mobile phone so they could do the reporting to us. This disease surveillance system could be used in other contexts or places. People today have mobile phones, even in the most remote places. More than 90% of people in Bangladesh have mobile phones, many of which are smartphones. So there is potential to develop this disease surveillance method further, maybe with a new app”

A case of non-severe diarrhoea cost the same as a community health worker

The cost of severe diarrhoea and cholera is known in the literature because these cases often end in hospitals where they are reported.

“We found that 90% of people with mild and moderate diarrhoea, they don't go to the hospital. So the costs and the consequences of these diseases are hidden within the community. The cost is above 50,000 USD annually in this community. It is a huge cost for such a community. So preventing diarrhoea will save a lot of money.”

The government of Bangladesh are trying to secure health equity to low-income groups through a new program, which includes pilots for health financing. Normally, health financing to the communities goes to the health care provided by the community health workers. One community health worker costs around 6 USD per person, which is the same cost associated with one episode of non-severe diarrhoea.

“If we can make the government understand this and use it in their health financing programmes, then we can get community health workers to provide health services including educating them about diarrhoea into the communities. Making health policies are a long-term process but at least now we have the data to prove that preventive measures can save money in this kind of community. This data is a valuable tool for us to move forward with understanding and research on the cost effectiveness and cost benefit.”

Although their findings might not be generalisable to all other low-income communities, there is a potential for scalability and applicability. At least to other low-income communities in Bangladesh as the characteristics are similar to the ones in East Arichpur where Rebeca did her studies.

Dense population is the main obstacle for improving health and hygiene

There are many obstacles for improving health and hygiene in low-income communities. The main challenge is the large and dense populations. But as Rebeca says, that is not really something you can do anything about as a researcher.

“You could look at several challenges but infrastructural changes is needed. In order to change things for the better on a community-level and not just household-level, the state and the government need to come up with new strategies and movements. Such movement is already happening in Bangladesh, where the government is very enthusiastic about changing health conditions for low-income communities in the next five-year plan.”

Another major concern is groundwater depletion:

“One of the issues that really made me concerned when doing this research was the depletion of groundwater in the cities of Bangladesh. Every year, we are pumping more groundwater up than is naturally restored. 50 years ago, the community I was looking at depended on clean surface water. Due to increased water usage, they had to introduce a submersible pump, which they have to dig deeper and deeper every year into the ground to get access to clean water. Something needs to be done here because the depletion of water resources is happening faster than water recovery such as recycling.”

Rebeca will defend her PhD in May-June 2021. Stay updated on our event website here.

About Rebeca Sultana

Rebeca Sultana has spent the past 20 years in the public health sector of Bangladesh. She joined the icddr,b in Dhaka in 2005 and has worked with public health research ever since. She is from the first batch of anthropology students from University of Dhaka and later got an European Public Health Master degree in international health focusing on health in emergencies. Her current PhD is in public health and epidemiology, which includes medical anthropology and health economics.

She started out in the development sector doing research particularly on emerging infectious diseases in Bangladesh, such as Nipah virus, avian flu and COVID-19. She is a cultural epidemiologist, involved in mixed method and anthropological research on risk factors, risky behaviours, outbreak investigations, context-appropriate intervention and method development, and evaluate different community based interventions.

- The Cholera Phone: Diarrheal Disease Surveillance by Mobile Phone in Bangladesh

- A Comparative Analysis of Vibrio cholerae Contamination in Point-of-Drinking and Source Water in a Low-Income Urban Community, Bangladesh

- Water usage, hygiene and diarrhea in low-income urban communities—A mixed method prospective longitudinal study

About the study

Combating Cholera Caused by Climate Change in Bangladesh (C5) is a multi-disciplinary study that examines the risk and effects of climate-induced cholera on water stress on household hygiene in Bangladesh. The objective of the research project is to provide a holistic understanding of low-income community life in terms of water stress, diarrhoea and cholera. The project included five PhDs looking at it from five different perspectives: public health, anthropology, two microbiology researchers and an environmental engineer. It is a joint project between UCPH, Dhaka University and icddr,b, funded by DANIDA.