After hard working days she rested by the beautiful Ebola River

It happened in the heart of Africa. In the mid-1970s. Two mysterious, life-threatening illnesses occurred, at short intervals. One came from a brand-new virus and killed lightning fast. The other was unknown and killed more slowly. The Danish surgeon did not know about this last virus during the five years she spent in the Democratic Republic of the Congo but in the end, it would cause her death.

Text: Helle Maj / Photos: Jørn Stjerneklar and Mayday Press / Translation to English: Thorkild Tylleskär

The long palm tree avenue suddenly appeared from nowhere in the middle of the rainforest. That's where Margrethe Rask - the woman everyone just called Grethe - came driving. The avenue first led her past an impressive Catholic church. This was the largest and tallest building in the city of Abumombasi. To this day, the church signals civilisation and higher powers, with its two towers and yellow bricks.

At the end of the avenue was the Missionary Hospital, a hospital area surrounded by flamboyant trees in full bloom. This is where Grethe Rask from the Danish small town, Thisted, had her daily residence for three years, from 1972 to 1975. But she had actually stayed in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (previously known as Zaire) once before. That was in 1964. But after one year, she had returned to Denmark to write her doctoral dissertation in gastric surgery and tropical diseases.

Now the Danish surgeon was back in the country, at the hospital she had lived at that time. It was a simple operating theatre, but it was clean and well-functioning. This was thanks to a senior politician who lived in Abumombasi and provided her with supplies.

But that was never enough. However, this did not prevent Grethe Rask and her employees from doing the work they were there to do. They only used what they had at hand.

A cotton piece and a flashlight

The anesthetist at the hospital had learnt to fix a piece of cotton under the patients' noses. If the cotton stopped fluttering, he knew it was dangerous. The surgery nurse, in turn, always had a flashlight available - if the power suddenly went off. Sterile rubber gloves were rare.

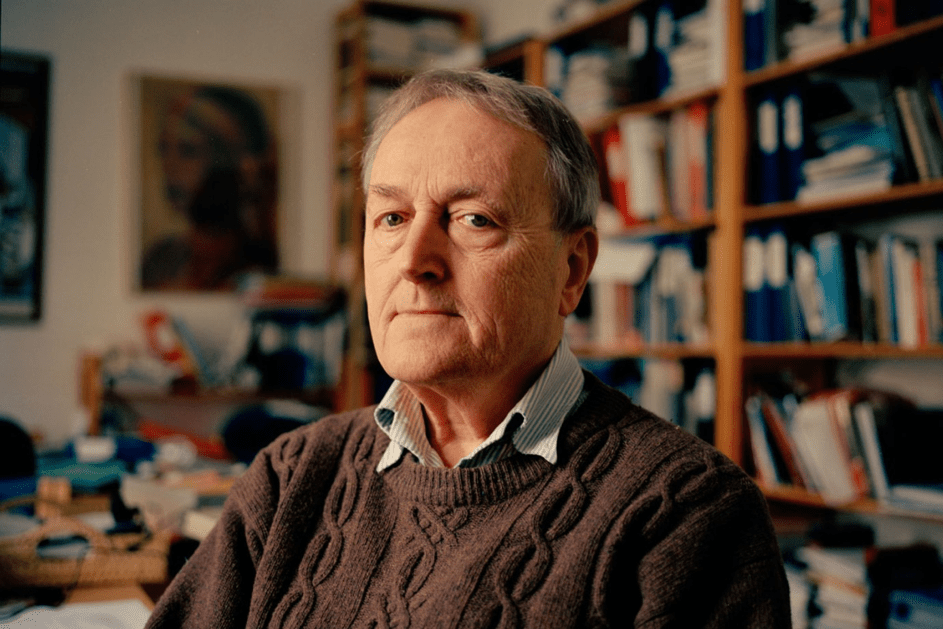

"Grethe often had to work without gloves during the operations, for example if it was necessary to pull out the placenta that was stuck. I also worked without gloves, and it happened that we ran out of disinfectants", says professor in global health, Ib Christian Bygbjerg (75), who was also stationed in Zaire in the 70s.

The hospital had no disposable needles, so the needles were used several times. But Grethe Rask saved lives. The public health in Abumombasi was not impressive, the malaria inexorably killed people and the rainforest offered all kinds of other diseases.

With warthogs on the menu

But the rainforest also brought food to the table. Many of the men of the village got food by hunting. For this reason, the doctors' dinner meals at the hospital often consisted of game meat. One night it could be a monkey, the next warthog or other exotic animals.

But the rainforest also brought food to the table. Many of the men of the village got food by hunting. For this reason, the doctors' dinner meals at the hospital often consisted of game meat. One night it could be a monkey, the next warthog or other exotic animals.

"I've been served cooked bats, which I ate. Everything else would have been rude to the locals", says Ib Christian Bygbjerg.

Grethe Rask was an energetic woman and much loved in Abumombasi. She ran the mission hospital as if it was her own little jungle clinic. And she always had a lot to do.

When she started to lose weight in 1974 and felt a fatigue, she blamed it on working too much. She didn't miss anything! And if she needed some rest, she would just drive down to the banks of the beautiful river that was about five miles from the hospital.

Became a surgeon in the capital

But something was wrong. Grethe Rask started to get infections.

In 1975 she moved to the capital Kinshasa, where she got a job as chief surgeon at the Danish-run Red Cross Hospital Clinique Kinoise.

"She was not a missionary, but a surgeon, and there was a great lack of surgeon specialists after most Belgians had left after independence", explains Ib Christian Bygbjerg.

It was at Clinique Kinoise that Ib Bygbjerg became acquainted with Grethe Rask in 1975. He soon became good friends with the 45-year-old woman who lived with another Danish, Karen Strandby Thomsen. She was the Deputy Nurse Supervisor.

They lived on the seventh floor of the high-rise building where the staff of Clinique Kinoise was accommodated.

On the seventh floor, without mosquitoes

"It was very popular to be on the upper floors because the mosquitoes rarely got all the way up there", Ib Christian Bygbjerg recalls.

He often visited the two women. They were also together in August 1976, when a mysterious illness broke out in a village not far from Abumombasi, where Grethe Rask had lived. People came to the village hospital with a fever before they started bleeding out of their noses, eyes, yes, out of all the pores of the body... After a few days they died.

The nurses at the mission hospital also died. 39 of them. And two doctors.

"We initially thought it was a Marburg virus, but it wasn't", says Ib Christian Bygbjerg.

It was something much worse. There was a new virus named after the river where Grethe Rask had liked to sit while relaxing in Abumombasi. The river was called Ebola.

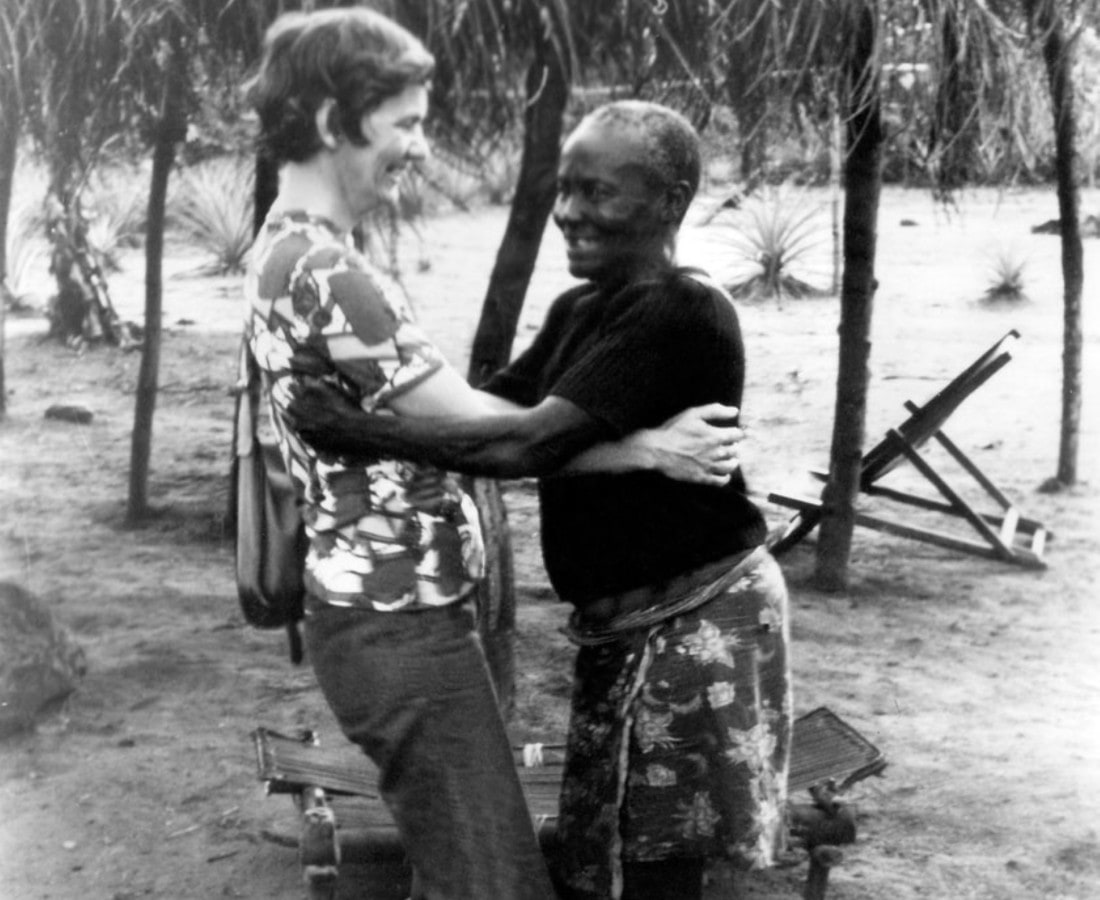

The hug

"Ebola killed the sister of my chief laboratory technician in Kinshasa, where she had nursed one of the sick nuns who had flown in from the Ebola area", says Bygbjerg.

The Congolese lab technician went to the sister's funeral, which caused Ib Christian Bygbjerg to impose two weeks of isolation on him. But before it got that far, the lab technician embraced him crying. To the doctor's great horror. At that time, it was already proven that Ebola was transmitted through body contact.

"Fortunately, it stayed with the fright", Ib Bygbjerg remembers.

Ebola killed 53 percent of those infected. 153 people were killed before the virus disappeared as mysteriously as it had occurred.

An even more dangerous virus

What no one knew at this time was that there was already an even more dangerous virus in the rainforest, a virus that would soon spread to the whole world and kill millions of people.

Neither did Grethe Rask. But she knew she was probably seriously ill. She had grown too thin. And the otherwise always energetic woman had long resisted the urge to just lie down and rest. When she was preparing a chicken in her kitchen in the tropical heat of Christmas 1976, she was again overwhelmed by fatigue and had to go to bed.

"My first thought was that Grethe was overworked. In addition, there were 30-40 degrees of heat and 100 percent humidity there. My next thought was that she might have got a gastrointestinal infection, but we found no signs of it, nor any signs of malaria. Then I considered everything from tuberculosis to leukemia, not least when she got swollen lymph nodes and was short of breath. And diabetes, when she got a fungus in her mouth", tells Ib Christian Bygbjerg about Christmas Eve in Kinshasa and the time that followed.

Couldn't breathe

Just over the New Year, Grethe Rask still felt better. The lymph nodes were not as swollen as before, so she continued to work. But during a holiday in South Africa in July 1977, she suddenly failed to breathe. Horrified and with an oxygen tank by her side, she flew home to Denmark.

At Rigshospitalet (the Danish "National Hospital"), the best specialists gathered around her to find out what she was suffering from. They tested for everything they could come up with. But the only conclusion they could agree on was that the patient was dying.

Her friend Ib Bygbjerg flew to Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine in a desperate attempt to find a diagnosis and treatment.

"I went to see my teacher, perhaps the very best tropical specialist and general practitioner we have, Dion R. Bell. But he also failed to make a diagnosis", he says.

Grethe Rask gave up and decided to travel from Copenhagen home to Jutland to die there. Her good friend from Zaire's time, nurse Karen Strandby Thomsen, also moved into Grethe Rask's little white-painted house outside Thisted to care for her

Impaired cell immunity

But Ib Bygbjerg refused to give up. He wanted to find the answer. What if they had overlooked something? A banal tropical thing they forgot to test for? He persuaded Grethe Rask to return to the National Hospital.

"She was admitted to another of my teachers, Professor Faber, in the epidemic department, where I worked. Faber had an immune test done that showed that her cell immunity was severely impaired. The remaining blood was stored in the tissue type laboratory", he says.

On December 12, 1977, Grethe Rask's body gave up. The official cause of death was bacterial pneumonia and a staphylococci septicemia.

The woman who had dedicated her entire life to helping others died in a hospital bed, just 47 years old.

"My alarm should have rung"

Two and a half years later, in September 1980, a 36-year-old agricultural engineer was admitted to Rigshospitalet. It turned out that he was suffering from a special form of pneumonia. The doctor Jan Gerstoft came from the State Serum Institute to try to find an explanation for the young man's diagnosis. He asked the patient about his life. The patient reported that he worked in the dairy industry and had been in New York for a trade conference. He also said he was gay.

Many homosexuals in Denmark had been open since the 1960s and 1970s, which is precisely why it did not raise eyebrows or medical concerns.

Later, Jan Gerstoft would acknowledge that the patient's homosexuality should have caused his alarm bells to ring. Only a few weeks earlier, he had seen another sick gay man, apparently inexplicably, but with a very aggressive outbreak of herpes.

In the years that followed, homosexuals with the most mysterious and unexplained symptoms entered the hospital. In New York, London, Paris and Copenhagen, all over the world.

Ib Bygbjerg also studied the homosexual patients and got a feeling of déja vù. It reminded him of Africa. He couldn't stop thinking that what was killing so many gay men, was the same thing that had taken Grethe Rask's life.

Grethe Rask's history of illness

Bygbjerg asked for permission to publish Grethe Rask's history of illness. Maybe her death could be a piece of the big puzzle? Maybe it was in her body that a new, deadly virus had debuted in Europe?

"You see tropical diseases everywhere, the other doctors laughed at him."

"But Professor Faber understood that it could be a tropical infection," says Ib Bygbjerg.

Only in 1983 - six years after Grethe Rask's death - did Bygbjerg get his dissertation "AIDS in a Danish Surgeon (Zaire 1976)" printed in the medical journal The Lancet.

The following year, her blood was tested for HIV in Denmark. The test was negative. In 1987, blood was shipped to the United States, where they tested with two different systems. Both tests were positive for HIV / AIDS.

Thus, it was established that the new "gay disease" was not new at all, nor was it a disease reserved for homosexuals. It was also determined that the disease came from Africa. And that Grethe Rask was one of the first Western European victims of the disease.

Origin of the viruses

The HIV virus was transmitted to humans via animals, science agrees. But how it happened, there are two theories about.

One theory is that people were infected by the virus during a polio vaccine trial in Central Africa. Substances from chimpanzee kidneys were used in the vaccine. The second theory - which is the most widespread - is that the infection was transmitted through human contact with wild animals. Like removing the chimpanzee's skin before preparing it for dinner.

Common to the three viruses, corona, Ebola and HIV, is that they are all so-called zoonoses, that is, they originate from wild animals. In areas where there is close contact between humans and wild animals, there is always a breeding ground for zoonoses.

Furthermore, all three viruses are rna-viruses, which means that they are faster to mutate than dna. This fact is important for how we are able to develop a vaccine against COVID-19. But we managed with Ebola, as Ib Bygbjerg notes.

Of the three viruses, hiv have killed the most. 32 million people have lost their lives to the virus. There is no vaccine against hiv but thanks to advancements in medical care and treatment, 37,9 million people are living with the chronic infection. Unprotected sex is still the most common reason for hiv infection.

Ebola is the most dangerous of the three viruses, as it kills 50% of the infected patients. In some outbreaks, 9 out of 10 infected people have been killed. But on the other hand, the infection rate is low as it does not infect via airborne particles. In other words, you have to touch an infected person to get infected. One Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014-2016 took the lives of 11.300 people. Monday 1 June 2020, the virus broke out again in the Democratic Republic of the Congo where it has killed 2200 people since August 2018.

The latest number of killed people by COVID-19 has surpassed 600.000. The virus has infected more than 15 million since it broke out in Wuhan in late 2019. More than 8,5 million people have recovered from the virus.

See the original article in Danish in Kristeligt Dagblad where it was first published on 9 June 2020.

See a second edition in Norwegian in Bistandsaktuelt, published on 19 June 2020.

Topics

News

Vaccine disguised as a virus tricks the body into stronger immunity

More women can now get answers about their hereditary risk of breast and ovarian cancer due to new genetic method